Knowledge Center

August 30, 2022

Pressure Ulcer Staging and Prevention Guide

Pressure Ulcers represent a significant nursing care problem, and their prevention is an important perioperative nursing goal. Studies show that 17% to 29% of the general acute care population will develop a pressure sore during their hospital stay. Of patients with pressure ulcers that originated during their hospital stay, nearly one-quarter of those ulcers are triggered during their surgical procedure in the operating room. In this article you will learn:

- Pressure Ulcers vs. Pressure Injury: What's The Difference?

- Pressure Ulcer Stages

- Pressure ulcers vs. Bedsores

- What is a Deep Tissue Pressure Injury (DTPI)

- Pressure injury causes and risk factors

- Pressure injury prevention devices

Pressure Ulcers vs. Pressure Injury: What's The Difference?

A pressure injury is caused by high pressure, continuous pressure, or pressure combined with shear and or friction, which occurs in the skin or the localized damage of the underlying soft tissue under the skin. A pressure ulcer, also known as Bed Sore, is a type of pressure injury; a lesion caused by unrelieved pressure that results in damage to underlying tissue.

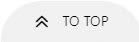

Most common pressure ulcer areas are bony prominences including the following:

- The back of the head and ears

- Shoulders

- Elbows

- Lower back and buttocks

- Hips

- Inner Knees

- Legs

- Heels

Pressure Ulcer Stages

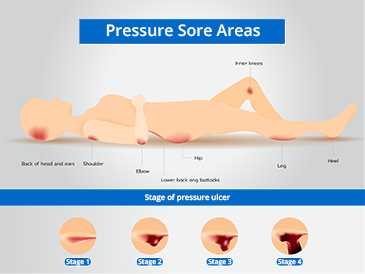

A national study by S. A. Aronovitch suggests that 9% of all surgical patients who underwent operative procedures lasting longer than three hours developed pressure ulcers. Immediate post-operative clinical findings of non-blanchable erythema of the skin progressed, within days, to more advanced stages of pressure sores.1

Another study by Hoshowsky and Schramm reported that surgical procedures lasting two and one-half to four hours doubled the risk, and a duration of four hours or longer tripled the risk of skin changes and increased the risk of pressure ulcer development by a factor of four.2

There are four distinct categories of pressure ulcers. They are staged to classify their severity and the degree of tissue damage observed.

Stage 1: Pressure Ulcer Stages

Stage I pressure ulcer exhibits an observable, pressure-related alteration of intact skin. It looks like reactive hyperemia, but it is not blanchable. (The skin does not turn white when pressed with a finger). Changes in sensation, temperature, or firmness may precede visual changes, but color changes do not include purple or maroon discoloration as these may indicate deep tissue pressure injury. Symptoms can be pain, burning, or itching. It is important to stop the pressure by changing the patient's position or using foam pads, pillows, or mattresses.

Stage 2: Pressure Ulcer Stages

Stage II pressure ulcer involves partial-thickness skin-loss of the epidermis and may include the dermis. The ulcer is superficial and looks like an abrasion, blister, or shallow crater. Symptoms are pain, swollen skin, warmth, and/or red. The sore may ooze clear fluid or pus. Stopping the pressure like in Stage 1 is important, in addition to cleaning the wound with water or a salt-water solution and drying it gently.

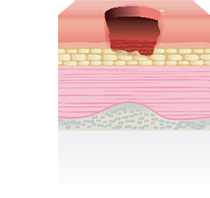

Stage 3: Pressure Ulcer Stages

Stage III ulcer is a full-thickness lesion. It involves damage or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue that may extend down to, but not through, the underlying fascia. It presents itself as a deep crater, with or without undermining of adjacent tissue. The sore has red edges, pus, odor, heat, and/or drainage. The tissue in or around the sore is black. The doctor may remove any dead tissue and prescribe antibiotics to fight infection.

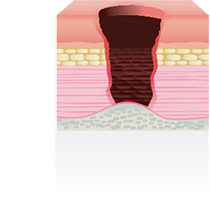

Stage 4: Pressure Ulcer Stages

Stage IV ulcer is a full-thickness skin loss with extensive destruction, tissue necrosis, or damage to the muscle, bone, or supporting structures, such as tendons or joint capsules. Sinus tracts and undermining of adjacent tissue may be present. The sore has red edges, pus, odor, heat, and/or drainage. This stage requires immediate attention, and the patient may need surgery.

In addition, there are two categories of pressure ulcers that are described outside of the staging classification system.

The Closed Pressure Ulcer

The closed pressure ulcer is a difficult lesion to diagnose. It has the appearance of a small wound, but inside is an insidious Stage IV-type lesion. Closed pressure lesions are frequently overlooked, with the result that patients who develop these can die from an infection. Most often, these ulcers are not detected until postmortem examination.

The Purple Ulcer (Unstageable Pressure Injury)

Ulcers that do not meet the criteria for any specific stage are classified in a catch-all category known as purple ulcers.

Pressure Ulcers vs. Bedsores

Pressure Ulcers are also known as Bedsores, Decubitus Ulcers, Pressure Sores, or Pressure Injuries. However, while Pressure Ulcers can develop during prolonged surgery or a hospital stay, a Bedsore generally develops on a person who has been immobile for long periods. It can be someone confined to a wheelchair or who cannot get out of bed.

What is a Deep Tissue Pressure Injury (DTPI)?

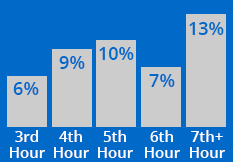

Deep Tissue Pressure Injury occurs with intact or non-intact skin with localized area of persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon, purple discoloration, or epidermal separation revealing a dark wound bed or blood-filled blister. Pain and temperature change often. Discoloration may appear differently in darkly pigmented skin. This injury results from intense and/or prolonged pressure and shear forces at the bone-muscle interface. The wound may evolve rapidly to reveal the actual extent of tissue injury or may resolve without tissue loss. If necrotic tissue, subcutaneous tissue, granulation tissue, fascia, muscle, or other underlying structures are visible, this indicates a full-thickness pressure injury (Unstageable, Stage 3 or Stage 4).7

Pressure injury causes and risk factors

Causes:

- Pressure is generally believed to be the most important of the extrinsic factors. For the surgical patient, the risk from pressure is normally from gravitational tissue distortion and compression located at the site of bony prominences.

- Skin shear is the mechanical stressing of capillaries and deep tissues when the body tissues move while the skin remains stationary. A patient's skin naturally holds to the bed surface while the patient is moved, so surgical patients encounter many opportunities for shear.

- Friction removes the top layer of the epidermis and can also create microscopic tears in the skin, making it more vulnerable to pressure and moisture.

Risk factors

- Length of surgery: Surgical times vary, but procedures lasting longer than 2.5 to three hours are significantly more likely to cause skin and underlying tissue damage.

- Patient position: shear will also occur when the OR table is tilted laterally, or in the Trendelenburg or reverse Trendelenburg positions.

- Positioning devices: If proper positioning devices are not used, chances get higher of patient shifting and therefore, skin shearing.

- Warming devices: Studies have shown correlation between body temperature and postoperative pressure ulcers and found that intraoperative control of hypothermia may reduce the incidence of postoperative pressure ulcers.11 See the STERIS Patient Warming System

- Anesthetic agents: Perioperative patients are at risk of developing pressure injuries since anesthetic agents interrupt normal relaxation and contraction of blood vessels and reduce perfusion at the site of the bony prominence.9

- Vasoactive medications: Studies have shown associations between type, dose, and duration of vasopressors (norepinephrine, epinephrine, vasopressin, phenylephrine, dopamine) and the development of pressure ulcers in medical-surgical and cardiothoracic intensive care unit patients.8

- Type of surgery: clinical experience, pressure injuries more frequently occurred in patients undergoing spinal surgery than in patients undergoing other surgeries.10

Additional risk factors:

- The pooling of fluids on the OR table under or around the patient can lead to maceration, where upper skin layers can be destroyed by moisture, making the tissue more vulnerable to friction or pressure.

- Rhabdomyolysis is a condition in which the breakdown and death of muscle fibers cause the leakage of potentially toxic cellular contents into the bloodstream. This condition is mechanically induced.

- Wrinkled sheets can also cause lines of high pressure and can be a source of post-operative pain, even if a pressure sore does not present. The wrinkles leave distinctive lines of pressure.

- Folded skin under tape can cause deep tissue lesions. When transferring and positioning obese patients, skin folds, especially in the legs, can also cause serious pressure ulcers.

Pressure Injury prevention devices

There are a growing number of positioning technologies that have been considered the standard of care for many years, including:

- Pressure management surfaces play a role in patient outcomes that is comparable to, if not greater than, the pressure management surfaces used in other areas of the hospital. See the STERIS Pressure Management pad solutions.

- Engineered hybrid multi-density foam mattresses absorb the patient's weight and redistribute pressure in specific areas commonly associated with OR-acquired ulcers. See the STERIS Hybrid Layer Technology tabletop pads.

- Gel Technology: molded gel positioner pads have become very popular as aides in posturing patients. Gel pads help nurses position patients and protect bony prominences and vulnerable nerves.

- Safety Straps, Immobilizers, and Positioners: some patient restraint products can help prevent mechanical stress caused by a patient's body shifting. The use of proper devices such as braces, supports, and straps help to reduce shear by reducing patient shifting. See STERIS Body Restraints offerings.

Summary:

OR-acquired pressure ulcers are an unnecessary tragedy. The first step to preventing them is recognizing that all surgical patients are at risk to develop them. Millions of anesthetized patients who have been subjected to sustained pressure have not developed pressure ulcers, but literally, all surgical patients have had the potential for one.

While using padding to redistribute pressure over bony prominence is important, it often is not enough as evidenced by the continuing prevalence of pressure injury in the surgical population. This is because even lower pressure over longer periods can cause a pressure injury. Additionally, padding and other manual and passive pressure management will depend on the care providers in the operating room. Active pressure management that aims to allow for the complete perfusion of tissue throughout the procedure can provide greater projection for the patient. Active overlays are also easy to deploy and can assist in achieving standardized processes that reduce variability.

To set a benchmark for incidence, a specific patient care plan should be developed and implemented in every OR so that patients are at minimal risk for suffering an ulcer. When considering a plan of care, patients at greater risk or subject to longer procedures should have active pressure management in place. Once this is implemented, you can establish a prevalence rate, justify your preventative care measures and determine actual costs for pressure ulcers that are started in the OR.

Contributors

Lena Fogle BSN, RN, CNOR

Senior Director Global Clinical Solutions, STERIS Healthcare

Lena is a seasoned healthcare leader with extensive experience leading complex perioperative environments as well as new program development, continuous process improvement, clinical outcomes, operational excellence, and stakeholder experience.

References

1 Aronovitch, Sharon A. Intraoperatively-acquired pressure ulcer prevalence: A national study. Journal of Wound Ostomy Continence Nursing, 1999, 26(3):130-136.

2 Hoshowsky, VM and Schramm CA. Intra-operative pressure prevention: an analysis of bedding materials. research in Nursing and Health, 1994, 17 (5):333-339.

3 The Use of an Alternating Pressure Surface to Reduce Intra-Operative Pressure Injuries in Complex Surgical Cancer Patients Kevin Andre S. Lim, BSN, RN, CNOR; Cori Kopecky, MSN, RN, OCN.

4 US National Library of Medicine. National Institutes of Health. Pressure Ulcers: Current Understanding and Newer Modalities of Treatment. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4413488/) Accessed 10/22/2018.

5 Merck Manual. Pressure Sores. (https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/skin-disorders/pressure-sores/pressure-sores) Accessed 10/22/2018.

6 Edsberg, L. E., Black, J. M., Goldberg, M., McNichol, L., Moore, L., & Sieggreen, M. (2016). Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised Pressure Injury Staging System. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 43(6), 585-597. doi:10.1097/won.0000000000000281 https://cdn.ymaws.com/npiap.com/resource/resmgr/npuap-position-statement-on-.pdf

7 Edsberg, L. E., Black, J. M., Goldberg, M., McNichol, L., Moore, L., & Sieggreen, M. (2016). Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised Pressure Injury Staging System. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 43(6), 585-597. doi:10.1097/won.0000000000000281 https://cdn.ymaws.com/npiap.com/resource/resmgr/npuap-position-statement-on-.pdf

8 Vasopressors and development of pressure ulcers in adult critical care patients: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26523008/2015 Nov;24(6):501-10.

9 Hwang HY, Shin YS, Cho HS, Yeo JS. Risk factors of pressure sore in patients undergoing general anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2007;53:79–84.

10 Luo M, Long XH, Wu JL, Huang SZ, Zeng Y. Incidence and risk factors of pressure injuries in surgical spinal patients: a retrospective study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2019.

11 Effects of warming therapy on pressure ulcers--a randomized trial - AORN J . 2001 May;73(5):921-7, 929-33, 936-8.