Knowledge Center

January 29, 2024

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding: Common Symptoms & Causes

Gastrointestinal bleeding is any bleeding that results from a medical disorder or severe condition of your digestive tract.1 The level of the bleeding present can vary and occur in the upper or lower GI tract. As there are various causes of GI bleeding and associated symptoms, physicians will evaluate the bleeding and treat it with different endoscopic tools and instruments. Learn about the common causes of GI bleeding, related symptoms, and preventative measures to avoid future bleeds.

What causes GI bleeding?

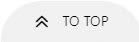

Peptic ulcers, including gastric and duodenal ulcers, are among the most common causes of nonvariceal upper GI bleeding. A GI bleed can appear suddenly or gradually, worsen over time, and vary in symptoms based on the location of the bleed. Common causes of gastrointestinal bleeds can also depend on the patient’s age and underlying medical conditions. For adults, peptic ulcers are the most common form of acute upper GI bleeding, while hemorrhoids and colon cancer are two common causes of lower GI bleeds for this age group.2 For toddlers, the most common cause of GI bleeding is anal fissures due to constipation or hemorrhoids.3 Patients with liver cirrhosis are at risk of upper GI bleeding due to lesions caused by portal hypertension.4

What is the difference between an upper and lower GI bleed?

The upper and lower GI tracts are separated by the ligament of Treitz – with upper GI bleeding occurring above the ligament of Treitz and lower GI bleeding occurring below the ligament. The ligament of Treitz suspends the distal duodenum and marks the junction between the duodenum and jejunum. This ligament helps to facilitate the movement of intestinal contents while also connecting the duodenum to the diaphragm and posterior abdominal wall.

Comparing both upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeds, upper GI bleeds are typically more common and result in higher morbidity and mortality rates among patients.5 Approximately 15% of patients with a presumed lower GI bleed are ultimately diagnosed with an upper GI bleed.7

What causes Upper GI bleeding?

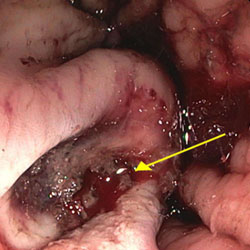

Upper GI bleeds are typically caused by peptic ulcers, hemorrhage, esophageal varices, and gastric varices, among other lesions. Esophageal varices account for up to 20% of all acute upper GI bleed cases. Varices are highly dilated, inflamed submucosal veins caused by portal hypertension. Gastric varices commonly extend from esophageal varices and result in inflamed submucosal veins in the stomach.

Other less common causes of upper GI bleeding include Mallory Weiss tears, Dieulafoy's lesions, and Boerhaave Syndrome.

What causes Lower GI bleeding?

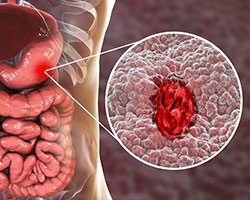

The most common causes of lower GI bleeding are diverticulosis, hemorrhoids, and ischemia.8 Diverticular bleeding is from ruptured, dilated arteriovenous vessels arising from the submucosal layer of the diverticula. While diverticular bleeding accounts for about 30% of acute lower GI bleeds, the precise location of the bleed can be challenging to find if the bleeding is not active at the endoscopy.9 Hemorrhoids are the second most common cause of a lower GI bleed, accounting for about 14% of causes.

Doctors use various types of therapy, surgery, or medication to treat a lower GI bleed, depending on the cause. Lower GI bleeds can appear as bright red blood or black tar in the stool.1

While typically less common, additional causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeds include inflammatory bowel disease, post-polypectomy complications, colon cancer, polyps, rectal ulcers, and vascular ectasia.8

How serious is a GI bleed?

The severity of GI bleeding varies depending on the type and cause of the bleeding. Less severe types of GI bleeding, such as hemorrhoids, may stop independently. However, significant bleeding requires medical intervention. If a GI bleed is left untreated, it may lead to anemia, hypovolemia, and shock. In more severe cases, untreated GI bleeds may cause irreversible damage or lead to death.6 If you notice any symptoms of GI bleeding, it is essential to consult a physician to discuss treatment.

Healthcare providers may use a risk stratification guide to determine the severity of an upper gastrointestinal bleed and help triage the patient to the most appropriate level of care. These guides include the Glasgow-Blatchford Score (GBS), AIMS65 score, and Rockall score.

The GBS score predicts the need for hospital-based intervention by looking at various patient risk factors, including hemoglobin, heart rate, and other factors like liver disease.10 Secondly, the AIMS65 score helps predict mortality and intensive care unit admissions by measuring risk factors, including albumin, age, international normalized ratio (INR), and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP).10 Finally, the Rockall Score is used for post-endoscopic assessment to predict rebleed rates, the need for further intervention, and mortality. This scale also looks at various factors and weighs them with a point scale, including age, pulse, renal/liver status, other diagnoses, and evidence of bleeding.10

How do you know if you have a GI bleed?

As internal bleeding is not always visible, paying attention to any other symptoms that may appear is essential. Physicians will monitor patients for symptoms such as epigastric pain, dyspepsia, lightheadedness, dizziness, syncope, and abnormal vital signs. Other common symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeds are cramps in your abdomen, paleness, shortness of breath, tiredness, rapid heartbeat, weakness, and fatigue.1 Other signs of a GI bleed may be present if you are vomiting blood, your stool is bright red, or your stool is black and tarry. Consult a physician if you suspect you may have internal bleeding and have any of these symptoms.

Signs and symptoms of a GI bleed can also vary by location. Below is an outline of common symptoms a patient may report that could indicate the source of bleeding.7

| Upper GI Bleeding | Lower GI Bleeding |

|---|---|

|

|

GI Bleeding Prevention and Treatment

If a GI bleed is detected, physicians will locate the source of the bleed to determine if surgical treatment is required. Pre-procedural interventions help to stabilize and resuscitate the patient, maintain organ function, and prep the GI tract for successful therapy. These interventions include intravenous (IV) therapy, blood transfusions, prokinetics, and high-dose PPI to decrease the stigmata of recent hemorrhage and the risk of rebleed. While nasogastric lavage used to be a standard therapy, it is no longer recommended as it was found not to improve the probability of finding a high-risk lesion on endoscopy and did not affect rebleeding or mortality rates.11

In addition to pre-procedural interventions, the timing of assessing a bleed and completing an endoscopy also affects successful treatment, morality and rebleed rates, and hospital length of stay. An immediate endoscopy occurs within three hours of presentation, an emergent endoscopy within 12 hours, and an early (urgent) endoscopy within 24 hours.11

Endoscopic management and treatment of GI Bleeding include a variety of techniques, including:

-

Injection therapy

Injection therapy causes vasoconstriction, sclerosis, or embolization. Epinephrine can be used for vasoconstriction, ethanol/polidocanol for sclerosis, and glue for embolization.

-

Mechanical therapy

Mechanical therapy consists of TTS and cap-based devices that physically compress tissue and the bleeding source. Standard tools used for this therapy include band ligation, hemostatic clips, and large defect closure devices like the Padlock Clip® Defect Closure System.

-

Thermal therapy

This type of therapy uses contact and non-contact forms of heat and energy to coagulate the tissue. Specific thermal therapy and devices include electrosurgery devices, monopolar and bipolar energy, heater probes, APC, and hemostatic grasper.

-

Topical therapy

Topical therapy consists of liquids, aerosol powders, and polymers applied to a bleeding site.

To help prevent future GI bleeding conditions, physicians recommend eating a healthy, high-fiber diet and limiting drugs, alcohol, and smoking.1

In summary, upper and lower GI bleeds can be caused by various diseases requiring different GI treatment devices and techniques. This article covers common causes of GI bleeding, patient assessment of symptoms and risk stratification methods, and endoscopic therapies for gastrointestinal bleeding.

Contributors

Lisa Stuart BSN, RN

Article References

1 “Gastrointestinal Bleeding.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 15 Oct. 2020, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/gastrointestinal-bleeding/symptoms-causes/syc-20372729.

2 California, Manouchehr Saljoughian, PharmD, PhD Department of Pharmacy Services Alta Bates Summit Medical Center Berkeley. “Gastrointestinal Bleeding: An Alarming Sign.” www.uspharmacist.com/article/gastrointestinal-bleeding-an-alarming-sign.

3 Barth M.D., M.P.H., Bradley. “7 Common Causes of Pediatric GI Bleeding, plus Treatment Information | Digestive | Nutrition | UT Southwestern Medical Center.” Utswmed.org, 7 Nov. 2019, utswmed.org/medblog/gi-bleeding-children/.

4 Odelowo, Olajide O., et al. “Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis.” Journal of the National Medical Association, vol. 94, no. 8, 1 Aug. 2002, pp. 712–715, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2594284/#:~:text=Patients%20with%20liver%20cirrhosis%20may.

5 Wilson, MD, Damien Jonas. “Causes of Bleeding in the Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Tract.” News-Medical.net, 27 June 2016, www.news-medical.net/health/Causes-of-Bleeding-in-the-Upper-and-Lower-Gastrointestinal-Tract.aspx#:~:text=Bleeds%20from%20the%20upper%20GI. Accessed 15 Feb. 2023.

6 “GI Complications | Kindred Hospitals.” Kindred, www.kindredhospitals.com/our-services/ltac/conditions/gi-complications#:~:text=Shock%20%E2%80%94%20GI%20bleeds%20that%20come.

7 AM J Gastroenterol March 2016; 1-16 “ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Patients with Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding”

8 UCLA-CURE Hemostasis Research Group database IBD inflammatory bowel disease

9 ASGE Guideline “The role of endoscopy in the patient with lower GI Bleeding GIE Volume 79, No 6:2014.”

10 GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY Volume 84, No. 1:2016

11 Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clin N Am 28 (2018) 261-275